The following article has been updated since its original posting on LinkedIn in December 2018. |

For many, Christmas is a time of year when we can slow the pace of our busy work schedule and honor the special people in our lives. Aside from its obvious significance to Christians, the holiday is appreciated by many secularists and people of different faiths for its charming cultural traditions and celebration of family. Although Christmas holds different meanings to people in today’s society, most universally appreciate Christmas for its symbolic theme of love and goodwill to others.

As a young Episcopalian, I was frequently reminded of the Second Greatest Commandment, “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.” For many it’s the quintessential ideal and ultimate example of Christian practice. Even outside Christianity, the concept of ‘agape’ (altruistic love of fellow humans) is regarded as one of the highest expressions of philosophic and spiritual living. Regardless of one’s religion or personal beliefs, most would agree that life feels pretty damn wonderful when one experiences other people with a genuine sense of deep connection unbound by the constraints of condition.

Unless one lives isolated on an island of narcissism, it’s natural to experience love for family, friends, and those who share our common opinions. It seems most of us also feel a natural degree of empathy and inner connection toward humanity at large. But what about the Omar Mateen’s and Nikolas Cruz’s of the world? People who commit such horrific acts as the massacres at the Pulse Nightclub or Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland.

This question arises occasionally in conversations when discussing the subject of love. In my day job, I work as a consultant specialized in managing risks of mass homicide…terrorism, workplace and school shootings, and similar types of violence.

When this subject arises, I like to begin with the word, Empathy.

Empathy is defined as “The ability to understand and share the feelings of another.” With this concept in mind, it’s quite obvious we cannot experience genuine empathy (the precursor of agape) if we view mass killers as ‘evil monsters’ beyond sensible understanding. So let’s start with that line of inquiry…

What really differentiates us from the mass murderers of the world?

Almost all acts of mass homicide are characterized as predatory aggression resulting from a process of ideation, planning, and preparation. The phrase, “He snapped,” is largely a myth. Although acts of mass homicide are often triggered by events, such as terminations or dismissals from school, the pathway to violence is typically established long before the carnage commences.

Although the pathway to mass homicide is largely universal, the motivation for violence is often different between terrorists and non-ideological perpetrators.

Terrorists rationally adopt the use of violence to further an ideological goal. The key characteristic distinguishing a terrorist from any other idealistic visionary is that the terrorist views the use of violence as necessary, morally sanctioned, and values their ideal over the lives of others (and often their own life too).

Sounds pretty messed up, huh?…Well, let’s pause for a second.

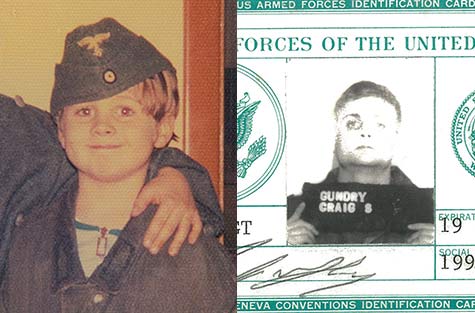

In early youth, I was enamored by the hero myth and American ideal of global freedom. I was a true product of Cold War era idealism and cultural suggestion that being a warrior was the ultimate expression of masculinity. And immediately after high school, I joined the Army. During those days, I would have killed any enemy soldiers as instructed and with a conscience cleansed by the noble aim of saving humanity from communist oppression.

When I look at it closely today, perhaps the only fundamental difference between me in those Army days and the terrorists of this world are the specific ideals motivating violent intent, and the rationale for distinguishing which human lives are valuable from those that are not. The individual ideals and beliefs were different, but the underlying mechanics are exactly the same. We both perceived violence as justified and valued an ideal as greater than human life.

So what about those who never wore a uniform?

Well, I propose mass killers aren’t fundamentally much different than you too.

Most non-ideological mass murderers align with Dr. Park Dietz’s definition of a pseudocommando. These individuals often evolve from angry, narcissistic personalities and harbor perceived injustices as a grievance for revenge. Violent fantasy becomes a refuge for the pseudocommando’s damaged ego and provides a sense of power and control. And without intervention, rumination and fantasy may become obsessional until a stage where violent fantasy becomes a template for action. If this progression continues unabated until nihilism takes place, commitment to violence is affirmed and often commenced in a planned manner or initiated by a trigger event.

So what does any of that craziness have to do with you and me?

Well, perhaps the pseudocommando’s pathology is nothing but an exaggeration of behavior we witness every day in most human beings.

Starting with narcissism, it seems most people spend the majority of life viewing the world through a subconscious prism of “What does it mean to/for me?”

In essence, we find ourselves perpetually motivated by desire for the ‘good stuff’ (pleasure, comfort, approval, attention, accomplishment) and seeking to escape the ‘bad stuff’ (pain, discomfort, disapproval, rejection, failure).

And if we watch closely, we can see how these primal impulses dominate our attention and behavior.

Now I suspect these polaric driving forces served a great value in evolutionary survival. Perhaps they’re the reason we derive pleasure from sex and eating calorie-rich foods, or seek warmth when our body temperature drops low. But in the modern world, these subconscious urges often result in a rollercoaster of irrational wants and fears resulting in all manner of mayhem. Just look at some of the things that stress people today…“Do I look good in that picture on Instagram?”, “Will people disapprove if I go to the store without doing my makeup?,” “Will my kid be a future failure because she got an F in math class or dyed her hair blue?”

When I discussed this matter with a friend recently, he responded by countering that his main focus these days was his company and family. Note the word “his” in this situation. Perhaps his attention was not centered on his personal desires and fears, but “his” company and family had become extensions of his identity by virtue of possession (“I” by association).

I am sure a few reading this may be offended by the notion that people are narcissistic in varying degrees. If you disbelieve me, great! Skepticism is the best launching point for using the scientific method. Try an experiment to disprove the hypothesis.

Experiment I

For the next few days, consciously observe how often you use the word “I” and “my” in thought and conversation. While at it, observe how much attention you devote to things that suggest possible reward or threaten harm.

Experiment II

(OPTIONAL)

Over the next week, observe what initial feelings arise when people approach you with a problem, bad news, or inopportune demand.

Another defining characteristic of the pseudocommando is “injustice collection.” This can also be described as held-resentment or more simply stated…Blame.

Here’s another area where maybe we don’t differ so much from the pseudocommando. Most people can’t navigate a single waking hour of the day without experiencing blame to some degree. It usually begins early when we blame our kids for leaving the milk out overnight or blame ourselves for misplacing our keys. This blame circus then continues through the day and up to the time we go to bed when we blame a stressful work situation for insomnia or our spouse for hoarding the bed covers.

I recently conducted a few experiments while having conversations with people and counted how many times someone expressed blame and its related behavior, complaint. I lost count after thirty minutes!

If you don’t believe me, great. Try an experiment…

Experiment III

Over the next few days, observe how many thoughts or statements you make in conversation expressing blame or complaint.

(Tip: Keep a counter handy!)

Experiment IV

(OPTIONAL)

If you have difficulty observing your own thoughts and behavior, go to a coffee house and sit next to a group of people and eavesdrop on the conversation. Make a game of counting how many times you hear people complain or blame.

Experiment V

Observe how often blame and the emotions that often accompany blame (e.g., annoyance, anger, guilt, resentment, etc.) actually change past events or improve situations.

In the end, perhaps the only difference between the average Joe and the pseudocommando is the degree of attention and importance devoted to blame.

So where does this blame stuff come from in the first place?

It seems blame is just a default cognitive response to situations where perceived reality doesn’t match our ideal (our vision of what ought-to-be). And this discussion point circles us right back to beliefs and ideals.

As satirized in that Walgreens commercial, we humans seem stubbornly committed to the imaginary concept of a “Perfect World” and spend a noteworthy chunk of time and energy trying to ‘fix’ what is, worried, or otherwise spinning our wheels in frustration.

Here’s another fun experiment…

Experiment VI

Choose an uneventful weekend and write an essay about your “Perfect World.” Just let it flow in a ‘Finnegans Wake-style’ of whatever nonsense comes into mind. Really put some heart into it! Exhaust this exercise well and note any realizations that emerge.

Here’s some old examples from Craig’s Perfect World…

All traffic lights turn green as he approaches intersections.

All cigars taste like black pepper and cocoa.

Mosquitos never bite.

Presidents are emotionally intelligent and unify the nation through their leadership.

All women are petite brunettes with specific features and find him sexually attractive.

...and his wife is okay with that too.

And so many more, their name is Legion.

When we really peel the onion to its core, perhaps the only difference in motivation between us and the mass killers of the world are the specific ideals that occupy and fascinate our imagination.

Well, maybe the problem is simply that mass killers have delusional (or incorrect) beliefs and ideals.

After all, my beliefs are the right beliefs!…My perspective of reality is the true perspective of reality!

When conducting threat assessments, we emphasize focus on understanding how a person of concern perceives a situation (such as bullying or mistreatment by others) over just the facts of the situation itself. What the subject thinks is going on (in essence, his or her perspective of reality) is ultimately what matters in identifying a possible accelerating motive.

Virginia Tech shooter Cho Seung-Hui wrote an extensive manifesto detailing his perceived persecution by people over the years. When investigated later, no one in Cho’s life ever remembered him being mistreated in any way.

Eliott Roger, responsible for the 2014 Isla Vista attacks, wrote a 137-page autobiography describing his hate for all girls because they didn’t want him, and men for having the girls. Perceived sexual rejection was his primary grievance for revenge. From the way Elliot described the situation, you would think this rejection stemmed from some condition of extreme unattractiveness such as obesity or physical disfigurement.

Quite the contrary, he was a good-looking kid.

It was basically all in his mind.

And that last statement, “all in his mind,” brings up a critical point in this discussion.

Most people approach life with the belief that they experience reality as objective truth. When in fact, all experience of reality is a constructed mental process influenced by countless subjective variables.

In waking states, information is received through sensory organs and processed into a mental image of physical reality. This sensory data is then interpreted through an unconscious cognitive process to provide context actionable for functioning. And belief plays a tremendous role in that final composite experience of reality.

Belief gives birth to ideals. And ideals give birth to judgement. And judgement, in turn, dictates how we value, relate, and react to our environment. It’s the complex prism through which everything we experience occurs.

Belief is defined as “something one accepts as true or real; a firmly held opinion or conviction.” Beliefs frame the architecture of what we interpret as reality. Without them, we couldn’t function as human beings. In the absence of complete knowledge, we need to operate on some degree of assumption.

It seems where we get tripped up in life is when we hold our beliefs as empirical truth, rather than simply acknowledging belief as confident hypothesis. It’s easy to point at Cho Seung-Hui and Elliot Roger and label their beliefs as delusional. However, how many times in our lives do we pridefully defend beliefs that we later discover are untrue?

If the previous point wasn’t obvious, here are a few experiments to try…

Experiment VII

Reflect on how many times you wrongly held something to be true. It’s easy to remember major examples which resulted in undesired consequences. But if you observe closely, you may notice that it probably occurs on a daily basis.

Experiment VIII

Knowledge is defined as “facts and information acquired through experience.” With that definition in mind, ask yourself how much of what you regard as knowledge is actually unproven belief. Contemplate this for a while and you may discover something huge.

It seems there’s another underappreciated fact about human behavior: Whatever you, I, or the mass killer does is perceived as being right or justifiable at the moment it’s done. Now we may feel conflict coming to that decision and we might feel differently five minutes later, but at the moment we act, the action is perceived as right or justifiable.

Don’t believe me? Try an experiment…

Experiment IX

Reflect on how many “regretful decisions” you made in life where you later asked yourself, “What was I thinking?”

And that last point brings us to the most provocative idea in this essay…

Not only does the killer perceive their act as right or justifiable at the moment it’s done, but perhaps it was the only thing he could do at that moment considering all factors of influence.

When we blame mass murderers and ponder how someone could commit a horrific act of violence, we often speak with the assumption that the killer acted with a conscious choice. Yet if we observe carefully, it seems most actions executed by human beings are largely dictated by personal conditioning (e.g., beliefs, ideals, gain/escape impulses, etc.) and circumstances that provoke or influence that conditioning.

In essence, something ‘pushes our buttons’ and we react. Sometimes life pushes a ‘happy’ button, other times an ‘angry’ button. But most people seem to live from button-press to button-press with an inner experience largely dictated by circumstance.

When circumstance takes form as a suggestion promising something desirable or threatening harm, we often behave quite predictably in accordance with our conditioning. This power of suggestion can be witnessed everywhere in the form of advertising, sales, politics, leadership, religion, education, etc. I know a few marketing professionals, CEO’s, and retired spies who can strongly testify to this fact.

Consciously or not, we all know this truth and use it every day to our advantage when interacting with others. But when it comes to us personally, people often stand in denial.

Now if the notion of behaving mechanically offends you, make note of that feeling of offense. Did you consciously choose to feel offended? Or did the words in this article dictate your inner experience?

Better yet, try a real experiment…

Experiment X

Make a conscious decision to be continuously happy for the next three days. Make up your mind that nothing or no one can push your buttons. Attempt to disprove the hypothesis proposed here.

Once we understand how people function, we may begin to see that the killer’s conditioning resulted directly from a lifelong chain of seamless events beginning at birth and right up to the moment he picked up a gun or strapped on a suicide vest.

And that principle seems to be true for all of us!

For the author, the chain started in August 1968 in a Pennsylvania hospital and continued through fifty years of interconnected experience right up to the moment of writing these words tonight.

So what does any of this have to do with loving a mass murderer?

A poet once wrote:

“Your task is not to seek for love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it.”

Perhaps there’s a profound wisdom in those words.

Most people approach life with a mistaken understanding…believing love is the product of favorable conditions which resulted in a spouse, or a child, or meeting others with similar beliefs and ideals. Some even believe they can willfully make themselves feel love to fulfill a religious obligation, only to feel guilty later when intention is insufficient. Love does not seem subject to the command of our desire. Rather…

Perhaps love is like light naturally radiating from a sun that never sets.

You don’t have to look for it. It’s always there, shining!

Only it’s often eclipsed as we stand with our back to it, obstructing its warmth and luminescence.

Instead, we often live like Plato’s cave dwellers, experiencing reality overcast and distorted by the shadows of our beliefs, our ideals, and ultimately, judgment.

So where do we begin?

Well, the experiments presented in this article are one possible place to begin.

Shine a light inward. Don’t worry about changing anything…Just watch.

Perhaps the simple act of observation can be a catalyst to something remarkable—a depth and availability of love you never knew was possible!